Groundwater

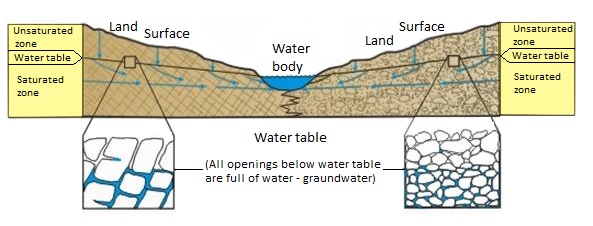

Water that fills the void space between the particles of soil or rock and other more open spaces in bedrock is referred as ground water. The boundary between the saturated zone below (where all the voids are filled with water) and the unsaturated zone above (where not all the voids are filled with water) is called the water table. There are two factors that make ground water available for human use - porosity and permeability. Porosity is the measure of the volume of void space (pore space), their size, and number, and permeability is the measure of how easily the water moves from pore space to pore space through a body such as rock or soil or how well they are interconnected. Porosity will determine how much water is present and permeability how fast that water can pass through material. When both factors are large enough, the medium, like soil or rock, can produce enough water usable by humans to a well placed within it, such material is then called an aquifer.

The highest yielding aquifers are typically in unconsolidated sand and or gravel layers. Aquifers composed of highly porous sandstone or highly fractured rock can also make good aquifers. Contrary to popular belief most ground water is not found in underground lakes or streams. Such large open cavities or caves only occur under very restricted conditions based on the type of bedrock - an example is limestone when it becomes eroded forming what is called karst terrain. Some sedimentary rocks such as clay and shale, metamorphic rocks and massive igneous rocks can hold only small amounts of water and do not allow water to pass through quickly. These types of formations are called aquicludes or aquitards and usually will yield little to no water to a well or spring.

How groundwater occurs in rocks and sediments.

References

Howard, J.M., Colton, G.W., and Prior, W.L., eds., 1997, Mineral, fossil-fuel, and water resources of Arkansas: Arkansas Geological Commission Bulletin 24

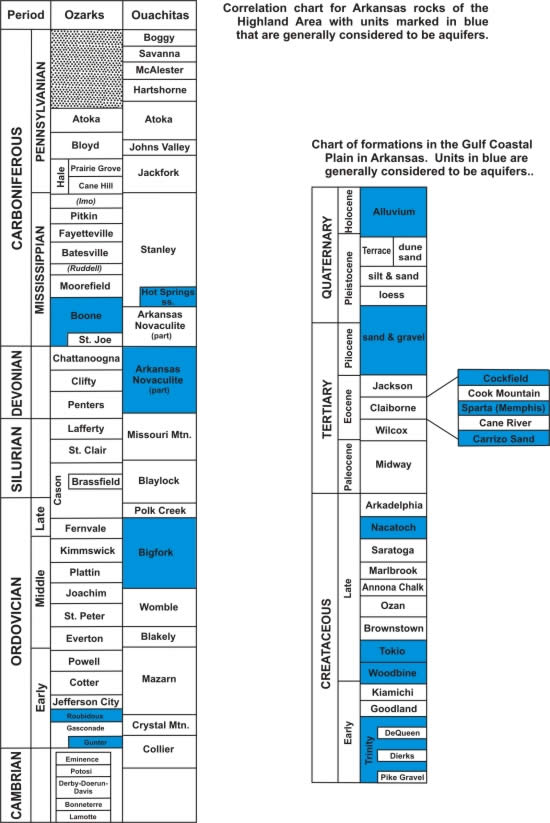

Much of Arkansas’ ground-water comes from Quaternary deposits of sand and gravel in the Mississippi River Embayment. Irrigation wells, with depths ranging from 100 to 200 feet, commonly produce 1,000 to 2,000 gallons per minute (GPM). Although usable for irrigation and some domestic uses, the high iron content of Quaternary aquifers makes the water generally unsuitable for human consumption in many areas. The deeper aquifers which underlie the majority of the Gulf Coastal Plain supply most domestic and municipal needs in this part of the State.

The Cockfield Formation of Eocene age crops out in south-central Arkansas. Southeast from its outcrop belt in Chicot and Desha Counties, the Cockfielsd is the only source of serviceable ground-water for communities in this part of the state. Locally, the formation ranges from 300-400 feet in depth and well yields range from 10-300 GPM.

Below the Cockfield are the very extensive sands of the Sparta/Memphis aquifer in the middle part of the Claiborne Group (also Eocene in age). The Sparta is used in southern Arkansas and Memphis in the northeastern Arkansas. The top of this major aquifer typically occurs at depths of 200-600 feet, and in some areas as deep as 1,000 feet. Individual wells may produce up to 1,200 GPM. Most communities in southern and eastern Arkansas use this aquifer as their source of supply. Other deeper units that are also used for public supplies include the Carrizo and Wilcox (Eocene) and the Nacatoch (Cretaceous) however these deeper formations may often contain saline water and therefore the area of usefulness is limited.

In the Interior Highlands of western and northern Arkansas ground-water supplies are more limited than in the Coastal Plain. Much of the Ozark Plateaus region is underlain by carbonate rocks, which are quite soluble in the presence of water. Solution by ground water has caused many large openings through which water passes so quickly that contaminants from the surface can not be filtered out. Signs of these openings are caves, sink holes, springs and lost stream segments. As a consequence, the water in shallow wells may not be suitable for human consumption without treatment. However, there are two important aquifers at greater depth – the Roubidoux Formation and the Gunter Member of the Gasconade Formation. Both are permeable sandstone and carbonate units of Ordovician age. These aquifers serve as the principal source of high-quality water for many communities in northern Arkansas. These formations do nor outcrop anywhere in Arkansas but instead outcrop in southern Missouri.

Because of the predominance of shale in both the surface and subsurface rocks in the Arkansas Valley and Ouachita Mountains regions, and the low porosity of many of the interbedded sandstones, few rock units qualify as aquifers. Because most wells yield less than 10 GPM, most communities rely on surface-water supplies. Among the more favorable units in the Ouachita Mountains are the Hot Springs Sandstone Member of the Stanley Shale (Mississippian), the Arkansas Novaculite (Mississippian-Devonian), and the Bigfork Chert (Ordovician). Lacking appreciable intragranular porosity, most of the available water in these units is confined to fractures caused by the mountain building processes in the Ouachita Mountains these same processes help produced quartz veins that are a possible source of at least domestic supplies in some areas. The only consistent source of ground-water in this region is the alluvium along the Arkansas River. The river derived sand and gravel deposits produce mostly water of irrigation but has and still has limited use as a community water source.

A spring is a place where ground water flows naturally from rock, sediment or soil onto the land surface. Its presence depends on the nature and relationship of permeable and impermeable units, on the position of the water table and on the land topography. Springs are present throughout Arkansas and consist of two general types: perennial and seasonal. Perennial springs flow year round whereas seasonal or “wet weather” springs dry up periodically, especially during droughts or long periods of minimal rainfall. In Arkansas these conditions often occur during lat summer and early fall.

Most of the perennial springs in Arkansas with the largest flows are located in the Ozark Plateaus region. With an average flow about 150,000 GPM, Mammoth Spring in Fulton County has the largest yield of any spring in the state. In this region, springs have historically been important community water sources. Most north Arkansas communities have now begun to abandon natural springs as water supplies because shallow springs are susceptible to contaminants from the surface.

Discharge from a cave opening at Blanchard Springs. Flow can vary between 1,000 to 103,000 gallons per minute depending on local rainfall (see picture on the left).

Perennial springs also occur in the Ouachita Mountains, most of these are considered “cold” (temperatures of less than 80 degrees F). Some of these cold springs are important sources of bottled water. However, there are areas of hot-water springs such as those of Hot Springs National Park where water temperatures average 143 degrees F. The quality or purity of spring water can vary from especially depending on which part of the state the spring occurs in, just like with surface water spring water from the Interior Highlands tend to be of higher quality than those that come from the Gulf Coastal Plain.

Mammoth Springs in Fulton County, Arkansas (see picture on the right).

Data on Springs in Arkansas, 1937

This is an unpublished compilation of information on springs in Arkansas arranged alphabetically by county. The information was collected during the late 19th and early 20th centuries (approximately 1885 - 1935). This work should be of interest especially for its historical descriptions of springs and their use during this time period. The only authorship noted is that it was compiled under the direction of George C. Branner, the then State Geologist of Arkansas.

References

Howard, J.M., Colton, G.W., and Prior, W.L., eds., 1997, Mineral, fossil-fuel, and water resources of Arkansas: Arkansas Geological Commission Bulletin 24

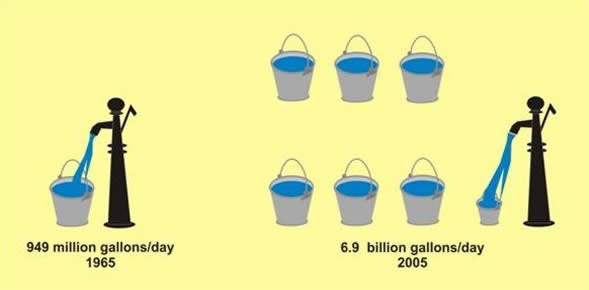

Ground-water use in Arkansas is about 7.5 billion gallons a day (2005) of which 6.9 billion gallons is used for irrigation alone. There is some 4.7 million acres of cropland in Arkansas that is irrigated and of this 84 percent is irrigated with ground-water. The growth in ground-water use has grown by some 632 percent from 1965-2005 just for irrigation alone.

Comparison of ground water use in irrigation from 1965 to 2005 (see picture on the left).

References

Holland, T.W., 2007, Water use in Arkansas, 2005: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific InvestigationsReport 2007-5241